Do We Still Need Cities?

Technology has radically changed how we work, now it’s transforming where we live

When Sridhar Vembu waved goodbye to his family and left the small farming village where he was born, the teenager joined millions of others across India who were migrating to the country’s cities, seeking the education and jobs that could help them escape generations of grinding poverty.

Vembu would go further than most. After receiving an engineering degree in Chennai he went on to Princeton for a PhD, and then to California where he founded Zoho, a wildly successful global software company that has made Vembu a billionaire.

Vembu’s life is a remarkable journey from humble beginnings to incredible success but it’s not an unfamiliar one.

Sundar Pichai, who now runs Google, remembers his family didn’t have a telephone until he was 10-years-old. His first trip on a plane, to attend college at Stanford, cost his father the equivalent of a year’s salary.

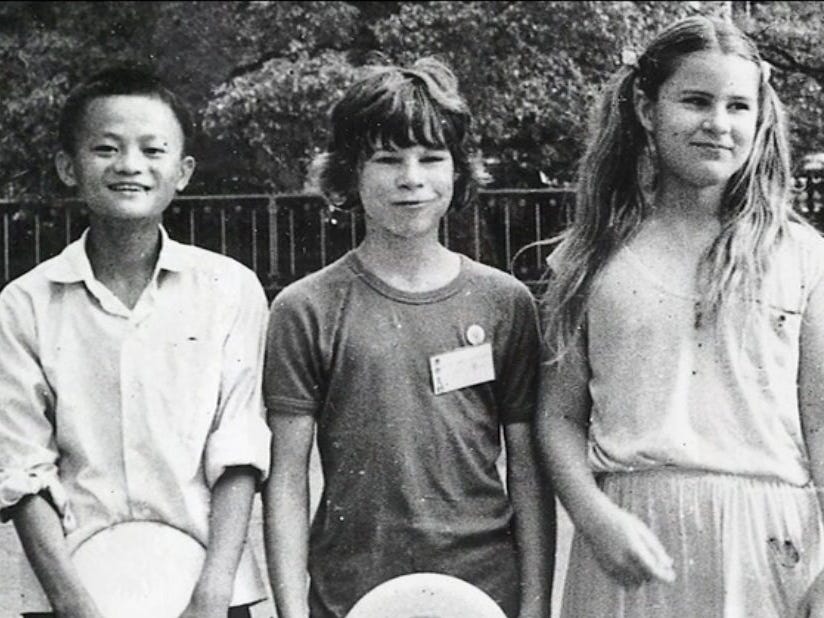

It was the same for Jack Ma. The founder of Alibaba may be worth almost $50 billion today but he was born into a poor family of musicians and spent his childhood collecting crickets. Ambitious from an early age, he would cycle to a hotel in the city where he could meet foreign tourists and learn English. His first job as a teacher earned him just $12 a month.

The rags-to-riches tales of Vembu, Pichai and Ma are woven into a larger story about an Asia that is on the move, where the rural poor are abandoning their villages and farms for the cities, and tracing the same pattern of migration that began centuries ago in Europe before repeating itself again and again across North America and Japan.

Over the next 30 years, about 700 million more people are expected to pour into the already-overcrowded cities of India and China.

While the benefits of urban migration are clear — they promise a better education and more income — the cost can be high.

Much like those European farmers who suddenly found themselves in urban hell-scapes of clanking machines and belching smokestacks, many of today’s Asian migrants are arriving in urban slums and shantytowns that are not that different from English cities in the 1700s.

These modern slums are plagued with inadequate shelter, frequent flooding, an absence of basic sanitation, dirty drinking water and disease. This is the grim reality for over 560 million people across Asia, afflicting a third of urban residents in India and Indonesia, and almost half of the urban population in Bangladesh and the Philippines.

And there may be very little we can do about it. Urbanization and squalor are the price that people have always paid to escape poverty and reach the first rung on the wealth ladder. It’s the miserable yet necessary path of development that’s been taken by all modern countries in the world today.

This is certainly the grudging consensus of experts at the UN. They do their best to alleviate the worst excesses of rapid urbanization but they accept hat this rising tide of humanity in the cities will not slow, let alone recede, until many decades into the future when wealthy urban residents will finally start leaving the crowded cities for leafy suburbs and hip small towns.

But not everyone agrees. A small yet growing number of contrarians believe this familiar pattern of misery isn’t going to repeat itself. They believe technology has flipped the script on development — that it’s going to disrupt urban migration much like new tech has disrupted our biggest companies and industries.

One of these contrarians is Sridhar Vembu, the young man who walked away from his small village in India to became the billionaire founder of Zoho.

Zoho has more than 10,000 employees in a dozen global offices from Silicon Valley to Singapore, Dubai, and Beijing; with a new headquarters being built from scratch on a 360-acre site just outside Austin, Texas.

But while other CEOs begin their day with chauffeured rides to downtown boardrooms, Vembu starts his day with a walk among green fields where farmers tend crops of brinjal, okra and tomatoes; where the trees are ripe with mangos and coconuts, and there’s a village well that’s ideal for an early morning swim.

Vembu has returned. He has retraced the journey of his youth that took him from the farm to the city, and now he’s back in the countryside, in a small village at the foot of the hilly and forested Western Ghats of southern India.

This is where he both lives and works. Thanks to India’s expansion of high-speed Internet access and a growing ecosystem of remote work technology, Vembu can run his multinational company from next to a grove of coconuts almost as easily as he would from an office in Silicon Valley or Singapore. Vembu is planning for many of his employees to leave the cities as well. Last year he opened a half dozen new offices in farming villages in India while another four offices are planned for small towns in Texas.

Zoho is one of the first companies to embrace remote work but it’s far from the last.

The list of organizations transitioning to remote work is expanding by the day. From Facebook and Twitter to financial services like Deloitte and State Farm, pharmaceutical companies like Novartis, and even governments like the state of Massachusetts; thousands of organizations are moving away from the office and into small towns, suburbs and homes across the world.

The change in Asia is even more profound. In India, for example, two million IT workers are now transitioning to remote work.

If the contrarians like Vembu are correct, urbanization in Asia is going to look very different from urbanization in the West. New technology will let countries in Asia leapfrog over stages of stages of development that took decades to unfold in the West.

We have a hint of what’s to come with the history of telephone. The West spent over a 100 years with fixed telephone lines and rotary phones. But many developing countries are skipping this century of development and leapfrogging straight to mobile phones.

It will be the same story for the Internet. While the developed world spent decades stringing cables across oceans and painstakingly laying that last difficult mile to peoples’ homes and offices, the developing world will have Starlink, a lighting fast Internet from space that can connect a log cabin in northern Canada as easily as an office in New York.

Technology will have a profound impact on cities, in both the developed and developing world.

People in San Francisco and Chicago will discover they can work just as easily in Fort Collins, CO, and Boise, ID, without putting up with crime, mediocre governance and high costs of living.

And the ambitious poor in Asia will realize they don’t need to put up with slums and shanty-towns to earn a living, go to school or experience electricity.

Actually, it’s already happening.

EDUCATION

Where it is

Only 30% of children in India finish high school.

Just 70% of the teachers haven’t mastered the subjects they teach.

While India produces some of the brightest students in the world, the education system is still fundamentally broken.

Where it’s going

Indian startup Byju’s just became the world’s biggest online learning company with 80 million students and a valuation of $13 billion.

In China, the tutoring app Zuoyebang just raised $1.6 billion while its rival Yuanfudao raised $2.2 billion.

Asia is now home to four of the world’s biggest online learning companies. The best schools of the future won’t be in the cities. They will be online.

INTERNET

Where it is

About 40% of people in China still lack access to the Internet. It’s almost 50% in India and 70% in Pakistan.

The Internet is the backbone of the modern economy. Cities have the Internet and many rural areas don’t, and that drives migration.

Where it’s going

In Southeast Asia last year about 40 million people logged on for the first time.

In India there will be 1 billion people online by 2025, up from 690 million today and 243 million just 6 years ago.

And now there’s Starlink, a constellation of 42,000 satellites in low-Earth orbit that will beam high-speed Internet to every part of the planet. Children in a small village in western Sumatra will get access to the best of online learning. A town in rural Philippines can be home to a help-desk for a Fortune 500 company. The Internet will be everywhere.

WORK

Where it is

China has 290 million migrant workers who left their hometowns for jobs in bigger cities.

The Indian capital New Delhi receives about 300,000 migrants every year.

The lack of opportunities in rural Asia has triggered a massive migration to cities where people can find jobs, education and basic amenities like electricity.

Where it’s going

Tata Consultancy Services, the world’s biggest IT company, is shifting three-quarters of its 460,000 employees to remote work by 2025.

Even banks are starting to abandon the cities. Barclays, DBS, HSBC and others are reducing their office space in Asian cities by up to 40%.

Throughout history, cities thrived at the expense of the countryside because they created the jobs and wealth that in turn produced our best schools, hospitals and other trappings of the modern world.

But this is coming to an end. Technology is stripping cities of their monopoly over progress. People all over the world are realizing that a squalid life in an Asian slum, or a gauntlet of crime on a late-night New York subway, are no longer the price we must pay for a good job or decent education.

Sridhar Vembu understood this before everyone else. And tomorrow morning, after his walk among the fields of purple brinjal and the trees laden with ripening mangos, as he slips off his sandals for an early dip in the local well, there will be people elsewhere in the world quietly reaching the same decision that Vembu once made.

They will decide to take a class online instead of traveling to a school in the city. They will say no to a downtown job that requires a one hour commute. Slowly, then quickly, millions of people will begin to realize that they would rather enjoy life in the countryside than endure another day in a city.

Great piece!

I admit I am more bearish on the idea that slums will be "leapfrogged". There are a lot of factors at play that draw people in -- and not all of them will change due to remote work.

I spent some time in Agbogbloshie in Ghana, for example. Many of its residents are fresh from remote areas elsewhere in the country. They speak only their local language and many cannot read. The odds don't seem high that they will easily transition to digital remote work, unless it's very low skill.

Slums don't arise just due to availability of work. Many developing world cities have corrupt and restrictive rules in place that make it hard to start a business, hard to hire and fire labor, hard to own assets, hard to open a bank account, and hard to build or acquire housing.

The businesses that poorer people undertake are often harmless, but illegal given the rules of their country. Slums are outposts of informality where people can trade and operate outside the purview of terrible official structures. There is a sense in which the very illegibility and disorder of slums is an asset when you are trying to avoid authorities.