The first race I ever ran was 100k

You learn a lot about yourself over a long race. Not all of them are good.

Hi everyone, this story is bit of a departure from my usual fare about tech, culture and business (I will send that later this week).

We were in a cow field near midnight, completely lost in the dark and too exhausted to talk.

Our lead runner had strayed from the hard-packed dirt of the trail and into bumpy tufts of long grass. Numbed by fatigue, we had kept blindly running and stumbling in what we thought was a curved route back to the trail, until someone finally croaked ‘stop.’

Now we huddled close together in the inky darkness. Someone pulled out a small pen light and a map but no one had the energy to look at it.

He moved the light slowly around our circle, stopping at one dirt and sweat-streaked face at a time. A tired face with eyes closed and snatching a few seconds of sleep. A face grimacing as leg calf muscles spasmed and seized. And another face blank and staring faraway into the night.

The cows snuffled indignantly in the dark around us — unseen but very close. We sipped water and did our best to eat granola bars that were too dry to swallow.

We had left the last checkpoint maybe an hour ago and still had hours of running at night before the trail would leave the rolling hills of the southern English countryside and dip down into a valley that led to a town and the finish line.

But at that moment the finish line could have been on the other side of the moon for all we cared. We couldn’t even find a trail that was within 10 or 20 meters of us. One more wrong decision and we would be wandering over these dark fields till morning.

And I had a little secret. I was in agony. The area along both sides of my groin and across each buttock felt like razor blades were cutting in to the skin. I wouldn’t realize why until after the race.

We drank some more water. Minutes passed and then, still without a word being spoken, we heard the unmistakable footsteps and wheezing of another group of runners.

Okay, it’s that way, and we staggered back to the race and more hours of hell.

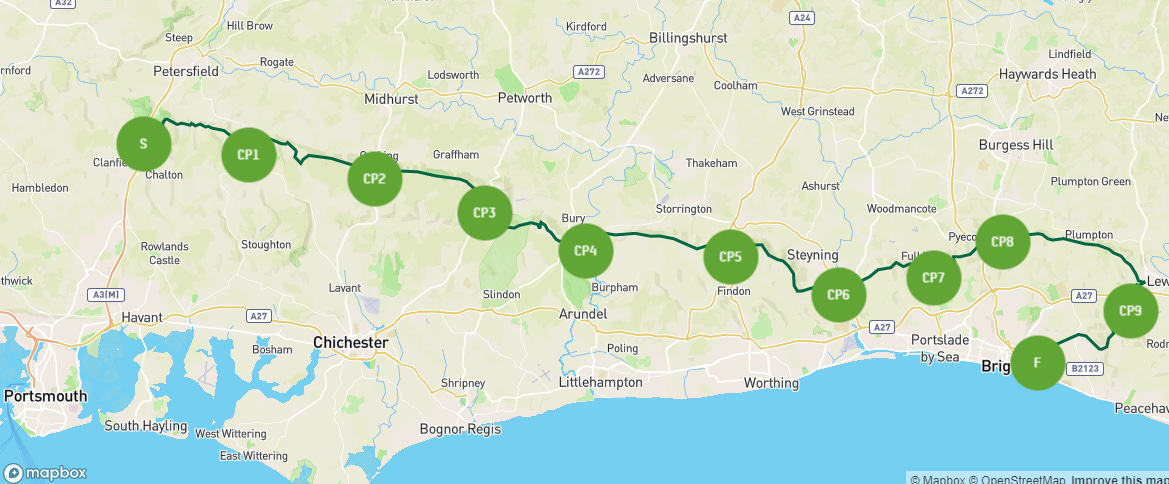

The Gurkha Trailwalker is a 100 kilometer race hosted by the famous Nepali soldiers who serve in the British Army. It winds its way through an area of England called the South Downs.

You run in groups of four people and the Gurkhas have never been beaten, even with elite rivals from the Royal Marines and elsewhere regularly having a go. The record finish time? Just 9 hours and 50 minutes.

I know all about the Gurkhas and their race now. But when I stood in that field at 7am on a Saturday morning to start the race, I knew almost nothing.

I had never run more than 12km during my jogs around the neighborhood. I had never entered an official race. And I didn’t even know the people I was running with. We had met a just days ago at the gym.

I had arrived in England four months earlier, moving to the London bureau of Bloomberg News after working in Asia for several years. From 7am every morning until 5pm or later, I was rooted to my desk and my keyboard, hammering out stories about company earnings, share prices and anything else that might interest our investor clients.

I didn’t like it. It’s sedentary, boring and repetitive work but Bloomberg paid well and London isn’t cheap.

The one thing that got me through the day was the gym just around the corner from the office.

It was an older gym at the bottom of a short, non-descript concrete stairwell that quickly left the noise of the busy street behind. It had wood-panelled walls that dated from the 1980s and a changing room where bankers swapped their expensive suits for squash rackets and headbands.

And me? I just hit the treadmill. Every day at noon on the button I walked up to a row of empty treadmills. I set the pace for exactly 13 km/h and just ran my heart out for 40 minutes.

Every single day it was the same. One treadmill and one fed-up editor pounding away the frustration of another long and tedious day at a desk.

They were clearly desperate.

Every year the gym organized teams for the Gurkha race but this year and at the last minute someone had dropped out. They needed a replacement and phoned around with no luck.

Then they took a look at everyone in the gym that day, desperate to add that fourth runner so one of the teams didn’t have to drop out.

And they saw me, flailing away on my treadmill. I imagine their conversation went something like this.

“What about that guy?”

“Who is he?”

“Dunno, but he’s on the treadmill every day.”

“So’s my mum.”

“Can your mum make it on Saturday?”

Sigh. “Right then, no choice I guess.”

They were desperate so they asked.

I was stupid so I said yes.

Why did I agree to do it? I still cringe thinking about it now, but when a couple of chiseled personal trainers appeared on either side of the treadmill during my cool down and started telling me about the race, I thought two things.

One, the flicker of pride. Wow, these super-fit guys are asking me to join their team. Ahh, the weakness of ego. How little I knew.

The second thing I thought— and still today I don’t know how I could be that dumb — but when they said 100k I didn’t laugh and tell them to take a hike. I quickly mulled it over and figured that if I could run 10k, and that there would be rest breaks every 10k or so, then it was just a matter of doing some 10k runs over a period of time. Wouldn’t be easy but, yeah, I could manage that.

And that’s how just days later I was at the start of a 100k race alongside Gurkhas and Marines with legs of iron, and three people on my team who I barely knew.

I learned a lot of things about myself that day — too many to count. But this is a short story not a book, so these are the top 5.

Sometimes slow is fast

At 6:55am and just minutes from the starting gun, the atmosphere was crackling with tension as some of the world’s scariest athletes shouldered their way to the front. My heart was thudding through my chest and my stomach knotted with fear. I wanted to race. But I was afraid to fail.

Then we were off. I forced my thoughts inward, settling in for the longest run of my life. Just one foot after another, I told myself. One after another, 10k at a time. The adrenaline waned, my breathing slowed and we started climbing the first hill.

I fixed my eyes on the top. Just keep running, don’t stop, never stop.

Then I heard my name. ‘Oi, where you going?’

I stopped. My team was behind me, walking. And laughing.

“You can’t run the entire bloody race, you numpty.”

We weren’t going to run the entire race? I didn’t understand it then, but after arriving at checkpoints at 30, 40 and 50k, I understood. The sprinters were quitting, and the pacers kept going.

Sometimes slow is fast.

People will always surprise you

I had briefly met the two personal trainers on my team but it wasn’t until the night before the race when all four of us got together. Both of the trainers were muscular and intimidating with six-pack abs and tree-trunk legs.

One was a wise-cracking south Londoner who would keep our spirits high at the lowest points of the race. The other was a rock-jawed South African who never smiled.

He was the natural leader of our small team, and the one who looked through me like I was just the fourth name on the list they needed to start the race. He told us when to stop and when to run. He was the guy we had to keep up with.

The last member of our team made me feel better. Not because he was nice. He hardly talked at all. But he was short and squat. A banker, not an athlete. Here, I thought, is someone who might quit before me. And that made me feel better.

The quitting came at the 50k checkpoint. But it wasn’t the banker. It was the South African. When we stood up to continue the next leg, he stayed down. His ankle hurt, he said. He was done.

It could have been the end of the race for us because the team has to finish together. But we got lucky. Another team had lost three members so their remaining runner took the South African’s bib number and we decided to continue.

We had lost our strongest member and it was only halfway. But who was the first of us back on the trail? The little banker. As quiet as ever.

Pride cometh before the fall

I was a weekend jogger who was happy stopping at red lights and taking my time re-tying laces. My runners were old and I wore shirts that were described perfectly by the Flight of the Choncords in their hilarious song Business Time.

You’re wearing that same old, baggy t-shirt with the stain on it

That you got from that team-building exercise

That you did for your work several years ago

But things had to change. Now, I was in a race. I was in THE RACE.

This called for a new look. So off I went to a sports section in a department store and got myself some flashy shorts and shirts. And then — because I was in a big-time race, you see — I bought some fancy spandex shorts-type things that hugged your thighs.

Yes, I nodded to myself, these are important. I have seen the personal trainers wearing them in the gym.

Now I had all the Gucci kit. Things were looking up.

It’s the morning of the race, and my new gear is all laid out when I’m suddenly confused. Do the spandex thigh-huggers go under my cotton briefs or over.

Can’t be under, that would look ridiculous. Okay, so they go over the briefs.

Hmm, it’s a bit uncomfortable but the pros wear them, right. And after a little tugging and stretching, I’m sorted.

An odd feeling started around the 5k mark. By 20k I was running with a short jerky stride to limit the chafing, and by 50k my transformation from weekend jogger to racing pro was complete — the spectators who were cheering us in to the checkpoint suddenly going quiet as I approached, legs splayed unnaturally far apart while my face twitched painfully with every jerky step.

Don’t be proud. It’s better to feel good than to look good.

The end is not always the end

We left the final checkpoint at 90k in a fog of fatigue and pain. Our cheery south Londoner had gone quiet a long time ago and was limping. His knee was blown and we took turns at his side. We were just shuffling along in the dark now. Our injured teammate’s steps were getting shorter and slower.

Someone said ‘look.’ Behind the next hill there was a smudge of light in the dark night sky. The town. Literally a light at the end of a dark tunnel, and I felt a flicker of emotion. Almost there.

The trail turned left and dipped. This final stretch would take us down from the hills and toward the finish. There would be people, showers and hot coffee. As the path descended steadily, our teammate became a little lighter and our shuffling picked up speed. We started to talk, offering encouragement.

We didn’t notice that the trail was getting darker again. Not at first. But then it became obvious. We couldn’t see the town’s lights and then suddenly the way ahead opened up to a broad expanse of dark fields and empty nothing.

Someone swore. We had taken the wrong valley. All of those eager, quicker steps we had taken to get down, would have to be retraced — slowly and painfully.

We hadn’t reached the end. We had created a new end, but much further away.

A moment of madness, a lifetime of regret

I don’t remember that climb back up the hill or searching for the correct trail. My next memory is taking a turn and then seeing just below us the bright lights of a small stadium and running track, a cluster of army trucks in a field and hundreds of people.

It was an incredible feeling of relief and happiness as we smiled and thumped each other on the back. But it was forever tainted by what I did next.

As we made our way down the last stretch, the banker suddenly broke away and ran. He flew down the trail and burst out onto the brightly lit track below, sprinting the last couple hundred meters to the finish line as hundreds of people cheered.

Like a hound after the hare, I lurched forward as well, but then stopped and looked back. The injured south Londoner was still limping, supported by the other teammate whose turn it was to help him.

He smiled. “Go on, mate, I’ll join you in a minute.”

So I turned and ran, pouring everything I had into a last, crazy sprint down the trail and out onto the track under the lights, the last 200 meters of 100,000 toward a cheering crowd and the finish line.

I had done it. Relief, joy and endorphins washed through me as I turned and walked back along the side of the track in front of the crowd, searching for someone I knew.

Then I saw them. My two teammates emerging from the darkness and into the lights of the track, arm in arm and supporting each other, one limping and the other shuffling.

And I was crushed. For a mad dash of glory, I had abandoned them. Left them alone still on a dark trail while I ran ahead into the light.

I walked back to them, and helped them finish. No one mentioned it. Maybe they didn’t care. But I did, and that feeling of crushing regret is as fresh today as it was then.

I have run a lot of races since that weekend. Marathons, half marathons, vertical marathons up skyscrapers and ultras that took me through long, dark nights in North America and Asia.

None stick with me like that 100k, where I discovered that I was a pretty strong runner — but a weak human being.

On that finish line under the lights, I saw who I really was. And I didn’t like it.